identifying the green zone

The essential question to be answered to identify entry into the Green Zone is "Can adequate alveolar oxygen delivery be confirmed?".

Confirmation: this will typically involve ensuring that ventilation with oxygen is occurring by the presence of a sustained ETCO2 waveform and/or rising SpO2 reading. When entering the Green Zone using a tracheal tube the ETCO2 trace must satisfy the criteria for ‘sustained exhaled carbon dioxide’ (see below).

Adequacy: the adequacy of alveolar oxygen delivery is not defined numerically but is instead assessed by asking "Is the patient likely to suffer harm from hypoxia if this level of SpO2 persists in the short term?". The absolute SpO2 value satisfying this criterion will vary according to the context.

The Green Zone refers to any situation in which adequate alveolar oxygen delivery can be confirmed and the patient is no longer at imminent risk of critical hypoxia. This provides the clinical team with time to pause and consider the opportunities available to them before further instrumenting the airway. These opportunities include optimising patient physiology, strategising regarding further interventions and mobilising resources.

Inability to intubate is an inconvenience. It is the loss of alveolar oxygen delivery resulting from repeated airway instrumentation that creates an emergency. Declaration that the Green Zone has been entered emphasises a key moment of situational awareness to the team. This has the potential to interrupt the process of repeated airway instrumentation that can convert the 'can oxygenate' situation into the 'can't oxygenate' situation.

“Inability to intubate is an inconvenience. It is the loss of alveolar oxygen delivery resulting from repeated airway instrumentation that creates an emergency.”

CO2 waveform morphology and ‘sustained exhaled carbon dioxide’

The morphology and amplitude of the ETCO2 waveform obtained with a facemask or supraglottic airway may vary considerably depending on the degree of airway patency and adequacy of the seal. These variations can be categorised for documentation purposes using the Concord Scale. Provided ETCO2 is consistently detected (indicating alveolar ventilation) and this achieves an adequate SpO2, these variations are not relevant to determining whether the Green Zone has been entered.

The morphology the ETCO2 waveform following tracheal intubation can also vary in ways that indicate conditions such as bronchospasm. While these are also not relevant to determining whether the Green Zone has been entered, it is not sufficient just to detect ANY sustained carbon dioxide. Certain minimum criteria must be satisfied that exclude the possibility of oesophageal intubation before declaring entry to the Green Zone using a tracheal tube.

The consensus guidelines for preventing unrecognised oesophageal intubation released by the Project for Universal Management of Airways and the international Airway Societies define 4 criteria that must be met in order to declare the presence of ‘sustained exhaled carbon dioxide’ (see below). If these are not met oesophageal extubation must be actively excluded. Satisfying the criteria for ‘sustained exhaled carbon dioxide’ is a prerequisite for declaring entry to the Green Zone using a tracheal tube.

“Satisfying the criteria for ‘sustained, exhaled carbon dioxide’ is a prerequisite for delaring entry to the Green Zone using a tracheal tube”

Relationship between the Green Zone & the SpO2

It is important to recognise that entry into the Green Zone is not synonymous with achieving a normal SpO2. Normal SpO2 may be maintained outside the Green Zone by preoxygenation stores despite an obstructed airway & absent alveolar oxygen delivery. Conversely following severe desaturation, recover of an ETCO2 trace accompanied by a return of the SpO2 level to only 85% would clearly confirm the occurrence of alveolar oxygen delivery. Irrespective of the exact value of the SpO2 reading, provided the oxygen saturation is considered 'adequate' in context, confirmed alveolar oxygen delivery always represents entry into the Green Zone and presents the team with the same opportunities to optimise and plan.

It should be recognised that, with the exception of acute airway obstruction, most episodes of advanced airway management commence from the Green Zone. Even in emergency situations where conscious state, oxygen saturations or airway patency may be compromised to some degree, necessitating some form of urgent airway intervention, the same opportunities exist to optimise, strategise and mobilise resources before this is initiated.

OPPORTUNITIES OF THE GREEN ZONE

In the Green Zone, the imminent threat of critical hypoxia has been removed and the patient is in a position of relative safety. This provides time to do the following:

Optimise:

Optimisation of patient physiology should consist of optimising both the oxygen saturation of the blood and the oxygen concentration in the alveoli.

Optimising the blood oxygen saturation minimises the immediate threat of harm from tissue hypoxia.

Optimising the oxygen concentration in the functional residual capacity of the lung increases the safe apnoea time which minimises the future threat of harm from tissue hypoxia in the event that alveolar oxygen delivery is subsequently interrupted.

Optimisation of haemodynamics should also be considered at this time as this may have been overlooked while trying to restore the airway, leading to compromise of oxygen delivery to the tissues.

Strategise:

Initial strategic options in the Green Zone can be discussed under three broad headings:

Maintain: maintain the airway by which the Green Zone was achieved and either proceed using this to manage the airway or withdraw ("wake" the patient) and use the current airway as a bridge to provide time for the patient to regain the ability to maintain their own airway.

Convert: an attempt can be made to convert the current airway to a more appropriate definitive airway which satisfies other secondary goals of airway management, without intending to leave the Green Zone. This can occur via one of the lifelines (e.g. converting a supraglottic airway to an endotracheal tube using an Aintree catheter) or via some form of neck ("surgical") airway under more controlled circumstances

Replace: this option involves a deliberate decision to leave the Green Zone, abandoning the technique by which alveolar oxygen delivery was achieved with the expectation that it can be restored by an alternate method. This amounts to re-entering the funnel of the Vortex.

Mobilise:

Having developed a strategy, the time provided by restoration of alveolar oxygen delivery can be used to assemble the appropriate resources necessary to facilitate the safe management of the patient. Resources include personnel, equipment and the potential to change the location in which airway management is taking place.

Personnel: this may include seeking the assistance of more senior staff, an anaesthetist, an ENT surgeon or simply an additional pair of hands.

Equipment: any specialised equipment for both primary and contingency plans should be made immediately available.

Location: there may be circumstances in which it is desirable to transfer the patient to a more suitable environment such as the operating suite before proceeding to definitive airway management.

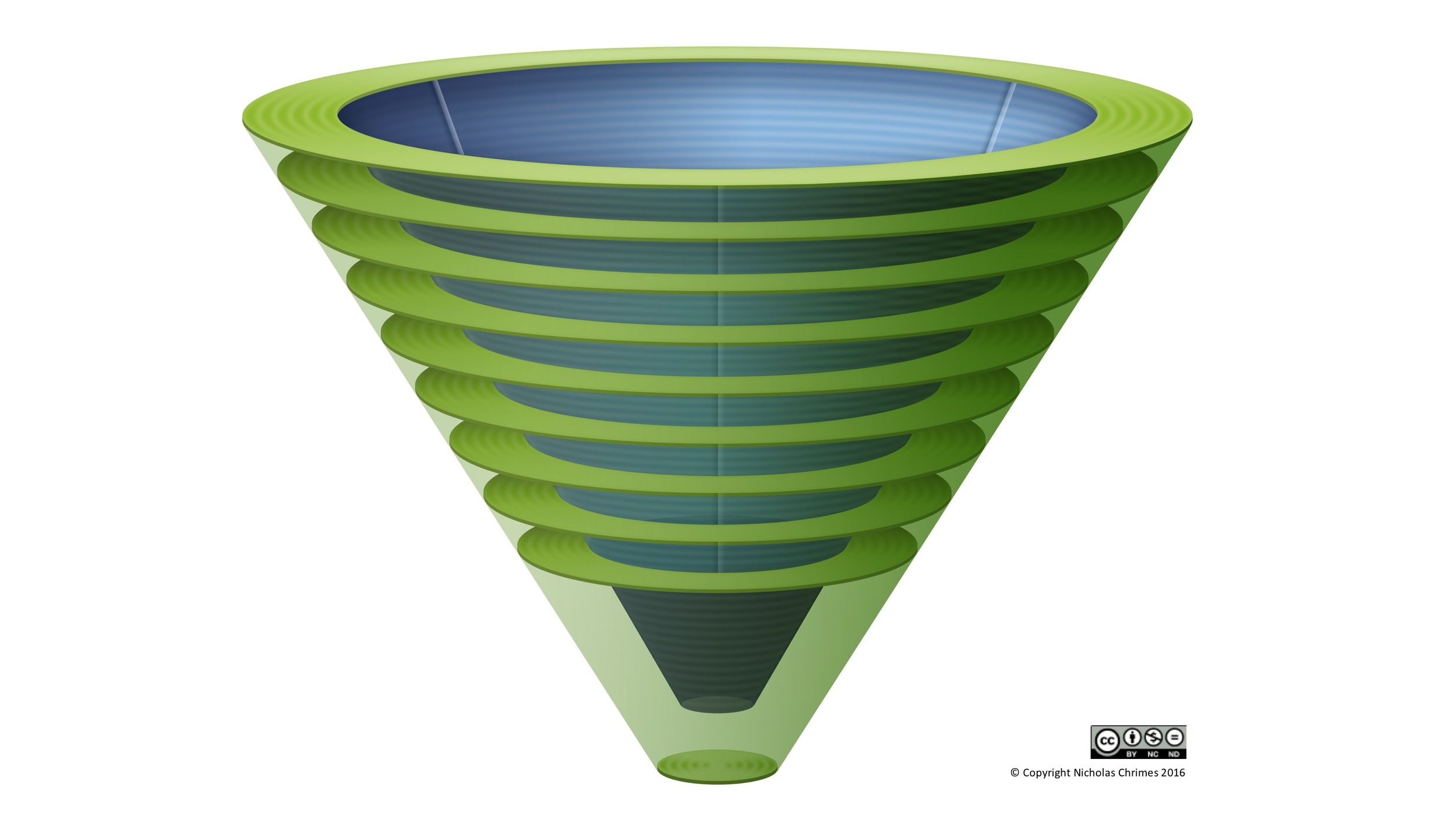

Entry into the Green Zone consistently provides the same opportunities. The horizontal rings that make up the Green Zone in the lateral, three dimensional image of the Vortex reinforce the opportunity to pause in order to optimise, strategise and mobilise that always exists here. The scope of options available to exploit these opportunities and what constitutes an appropriate strategy, however, depends on the context. The horizontal rings also allude to some of the context dependent considerations that influence planning in the Green Zone depending the tier at which it has been entered.

When the Green Zone has been entered with ease in an upper tier and multiple lifelines and optimisation strategies remain available, the option to 'replace' the lifeline that achieved the Green Zone and re-enter the funnel is much more reasonable. This is commonly the situation in elective intubations where, whilst waiting for a non-depolarising muscle relaxant to take effect, entry into the Green Zone is established via face mask. Once the patient is ready to be intubated, face mask ventilation is reliquished and the funnel re-entered with the expectation that endotracheal intubation will be straightforward and the knowledge that multiple other lifelines remain if this is not the case.

In contrast when the airway has been challenging, the process of exhausting multiple lifelines and optimisation strategies may result in spiralling deep into the Vortex before the Green Zone is successfully entered on a lower tier. In this situation, with limited options remaining and a much more imminent threat of needing to proceed to CICO Rescue if these are unsuccessful, the option to 'maintain' or 'convert' the airway by which the Green Zone was attained may be more pragmatic.

The Green Zone Tool prompts the team to consider key considerations for planning in the Green Zone. It is expected that the impact of each of these considerations on the decision making process is highlighted to airway clinicians during their training.

Whatever strategy is decided upon in the Green Zone, consideration should always be given to the contingency that the ability to achieve alveolar oxygen delivery is inadvertently lost. This should inlcude developing a strategy to complete best efforts at any remaining lifelines and an appropriate level of priming to perform CICO Rescue. Thus it is not sufficient to simply plan the next step in airway management while in the Green Zone. In developing a strategy the question that must repeatedly be asked is "What is the plan if that plan fails?"

WITHDRAWAL

'Withdrawal' is the term the Vortex Approach uses to refer to the process of 'waking' the patient. Withdrawal involves promoting restoration of spontaneous maintenance of airway patency and ventilation by the patient, such that they are able to remain in the Green Zone with minimal assistance. It represents an 'exit strategy' in management of the challenging airway which provides for a reduction in the level of airway support required to achieve adequate alveolar oxygen delivery - or at least an improvement in the adequacy of alveolar oxygen delivery at a given level of airway support.

The reason for this change in terminology is that the role of 'waking' during airway management is often obscured by its literal meaning. Using the term withdrawal emphasises the following:

That an immediate return to awareness and cooperativity is not necessarily required to exploit the opportunities this option provides, merely that the patient is able to resume contributing to the maintenance of their own alveolar oxygen delivery. It thus potentially extends the scope of situations in which this strategy might be perceived as being useful beyond that of elective anaesthesia patients.

That it need only be temporary and does not require negation of the need to subsequently proceed with airway management. The comment is often made that 'waking' is not an option in emergency contexts because the patient still requires intubation - but patients resuming maintenance of their own alveolar oxygen delivery, even for a short period, may provide a significant opportunity plan, prepare and ultimately minimise risk - even in circumstances in which there is a persistent need to undertake urgent airway management.

That it is a process requiring both time and a strategy of active interventions for its successful performance. This contrasts with the perception often conveyed by glib statements such as "if that doesn't work, I'll just wake the patient". Such statements imply that 'waking' is instantaneous 'flick of a switch' option and that the decision to do so therefore represents an endpoint in itself. Whereas 'waking' is often appended as the endpoint of a plan, 'withdrawal' denotes the next phase of the plan.

That it represents a reversal in strategy from either:

Pursuing methods to establish alveolar oxygen delivery that require an escalation in airway support

Proceeding with an airway other than the primary intended upper airway lifeline where alveolar oxygen delivery has been established in this manner.

When is withdrawal an appropriate option?

The notion of withdrawal as a time requiring process representing a reversal in strategy from actively escalating airway supports, has implications for the situations in which it represents a valid strategy. Many airway resources include reminders to "consider waking the patient" during management of the challenging airway without providing any guidance about the context in which this might be considered an appropriate course of action. The Vortex Approach advocates that withdrawal is only a viable option when in the Green Zone. It is not an option when stuck in the funnel of the Vortex, when alveolar oxygen delivery cannot be confirmed.

“There are two potential sources of harm relating to withdrawal: not considering withdrawal when in the Green Zone and considering withdrawal when not in the Green Zone.”

If best efforts at all three lifelines have been completed and alveolar oxygen delivery is unable to be confirmed then, even if the oxygen saturations are still maintained, the patient remains at imminent risk of hypoxia. In this situation it is necessary to establish and confirm alveolar oxygen delivery as efficiently as possible. Unless the patient is showing signs of immediate waking, the time taken for withdrawal makes this an unsuitable option to achieve this. Even if the oxygen saturations remain high, opting for withdrawal in these circumstances represents a gamble that the time to the patient recovering the ability to establish alveolar oxygen delivery spontaneously will be shorter than the time to critical desaturation. Often this will not be the case. When it is not possible to confirm alveolar oxygen delivery following best efforts at all three of the upper airway lifelines, the appropriate course of action is progression to CICO Rescue, not withdrawal. There are two potential sources of harm relating to withdrawal: not considering withdrawal when in the Green Zone and considering withdrawal when not in the Green Zone.